When John Boyd died in 2001, his friend and former pupil, Michael Scott prepared this obituary:

With the death of John Boyd, the Scottish art world has lost one of its most significant post-war painters. In an exhibition catalogue of 1996, I described him as ‘the quiet master of contemporary Scottish painting”, a judgment reinforced by time.

To know him and his work is to understand the appellation, for here was a professional life conducted with a complete absence of bombast, alongside the most serious mastery of the craft of painting, in the major fields of figure composition, still life, portraiture, the nude, and landscape. Here was a four-decade-long cultivation of an ever-deepening artistic vision. His reputation is now that of a painter’s painter, and his peers have no doubt that his creative powers were at their full height before his untimely death from prostate cancer.

He was born in 1940 in Stonehaven, Kincardineshire, where he was tutored in art at Machie Academy by James Morrison, who – being a practising painter (in Catterline at the same time as Joan Eardley) – was able to develop John’s skills and cultivate mature intellectual interests, particularly in Whistler, before his entry into Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen in 1958, where he trained under Henderson Blyth.

Exceptionally, John already had a clear image of himself as a painter. He was briefly a scholarship student at Hospitalfield College of Art in Arbroath in 1962, where he painted in the company of Alexander Frazer and the young John Byrne. The east coast would figure again in John’s art, but not really until after a long period of development in Glasgow, where he set up permanent residence.

Almost until 1990 he worked in an impressive range of teaching, from school to community arts training, but in truth painting was his only vocation; and for the past decade he had managed to pursue this without interruption.

His professional successes received confirmation in 1982 with his election to the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts and in 1989 to the Royal Society of Portrait Painters. In bodies such as these, and through 19 solo and innumerable group exhibitions, he displayed an oeuvre of a breadth and depth equalled only by the late David Donaldson and William Crosbie. Paintings such as that of The Smith Family in the 1994 Royal Glasgow Institute show must rank as among the best family portraits of the post-war period.

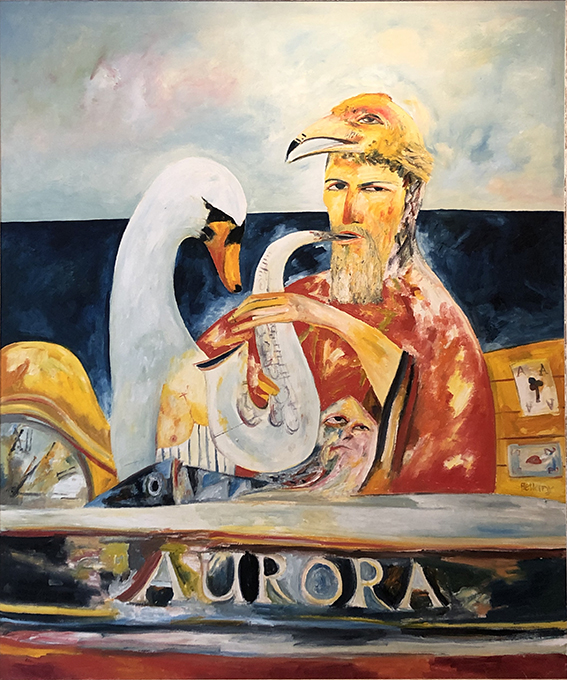

His still lifes (a consistent hymn to the language of paint) in themselves would be a singular achievement, but one exceeded by the large body of figure compositions which will certainly stand as his greatest contribution. There has at times been a tendency to view John Boyd’s painting as a succession of influences, a judgment which almost completely misses the point about the seriousness and complexity of his exploration of the nature of painting.

With no shred of anxiety, he allowed judiciously selected work by admired artists from Leger to Permecke to wash over him, confident that the immersion would always leave John Boyd intact. It was an extraordinary strategy of constant development and renewal through the confrontation of ever-deepening problems.

And it worked, because his paintings have achieved a remarkable clarity of vision and at times astonishing complexity of form. Groups of people in east coast landscapes – carrying symbolic objects, often boats, wholly absorbed in their activity, unaware of being beheld – evoke a harmony, peace, and silence

In a gentle, unconflicted universe: people who have achieved the kind of grace that John himself strove after and eventually found. His final exhibition, achieved despite severe illness, was in August 2001 at the Edinburgh Festival.