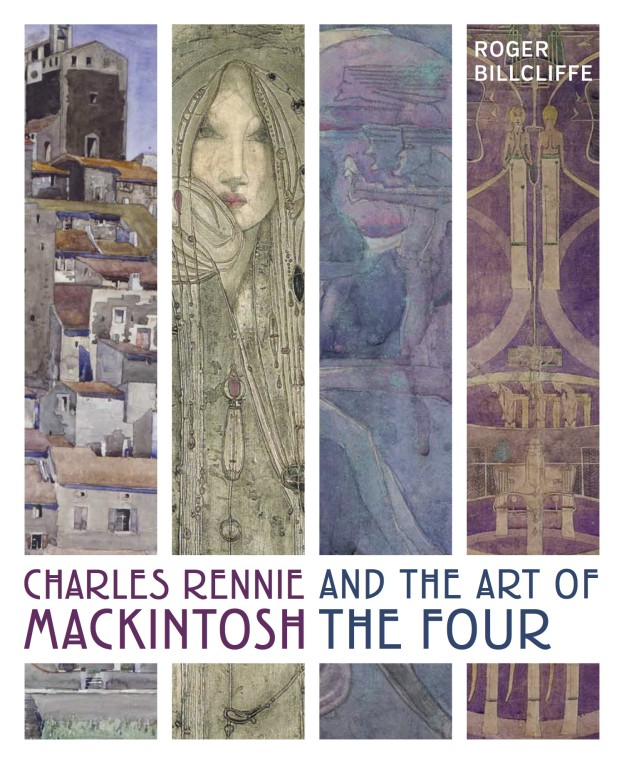

Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Art of The Four

Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Art of The Four

by Roger Billcliffe

Price: £20 plus P&P

EnquireCharles Rennie Mackintosh and the Art of the Four

Published by Frances Lincoln, London, £40

304 pages, 303 colour plates, bibliography, notes, index

Now out of print – a few copies remaining in Gallery stock

Now available at £20 plus p&p, while stocks last.

Email info@billcliffegallery.com to reserve a copy

The Four – the name given by their student friends to Margaret and Frances Macdonald, Herbert MacNair and Charles Rennie Mackintosh – have never been the subject of a wide-ranging critical study. I thought the 150th anniversary of Mackintosh’s birth was an ideal time to address the questions surrounding their work and look afresh at their relationships as artists – not just as friends and then married couples.

I have long believed that Mackintosh was not the leader of the new style that grew up in Glasgow, specifically at Glasgow School of Art, in the 1890s. He might have broken new ground with his watercolour The Harvest Moon and early decorative works but it was the Macdonald sisters, particularly the younger Frances, who led the way in turning these ideas into a new style. Mackintosh’s public career, however, both in Glasgow as an architect and in Europe as a designer, focussed attention on him and his later achievements and led to him being seen as the ‘leader’ of the group, particularly in Europe.

The precocious Frances – who enrolled at Glasgow School of Art at the age of 16 – invented their new vocabulary and perfected their novel palette, often collaborating with her sister Margaret and friend – and future husband – Bertie MacNair. It was almost certainly she who drove their move into decorative metalwork, pulling the others, including Mackintosh, with her.

In recent years, Margaret has been credited as the inventive force behind much of the work that she and Mackintosh produced after their marriage in 1900. I believe that this is a simplification, in fact the opposite of what actually happened. Margaret worked best as a collaborator, first with her sister or MacNair and later with Mackintosh in their famous interiors in Vienna and Turin. But Margaret’s individual pieces, watercolours and gesso panels made without the input of the others show a weakness of design and a reliance on repeating her successful imagery of the 1890s. Her collaborations with Mackintosh, however, produced her most substantial achievements, as a worker in gesso. These were surpassed only by a small group of watercolours, made some years after the gessoes were completed, and inspired by her emotional reactions to the deaths of her mother and sister.

Mackintosh had the longest career of The Four, effectively beginning as a watercolourist four or five years before the others, and then carrying on until 1927 with a superb collection of landscape watercolours painted in France after 1923. He was also more prolific than his friends and concentrated on a career as an artist after 1914, when they had effectively withdrawn from the art world. His fame as an architect has concentrated public attention on him but I hope that this book will show his role as, perhaps, ‘first among equals’ rather than a lone genius inspiring his contemporaries.